01: false harmony/discord (a case for stirring the pot)

On Responsible AI, collaboration, discourse and Rupture. #letthemcook

This past summer I worked on a research project about interdisciplinary collaboration, specifically in the context of “trustworthy & responsible AI”.

As a summer intern for Dr. Fazelpour, a Philosopher in the Computer Science Department at Northeastern University, we explored various definitions, considerations, and models of interdisciplinarity.

The hope was that by the end of the summer we, to some extent, would be able to make a framework to describe "key” antecedents and processes conducive to productive interdisciplinarity (i.e. whatever outcomes are relevant for a particular research team, company, policy discussion, etc.). The more I learned, the more questions came up for me. Like… what are “relevant outcomes”? And how are we defining, and measuring, “interdisciplinarity”? What is a discipline in the first place (this question genuinely haunts me still)?

While many questions remain unanswered, and others I’ll eventually write about here and/or in my academic publications, there’s one question I wanted needed to dedicate a Substack to: How do you know when interdisciplinary collaboration is “working”?

This is my working hypothesis: We know interdisciplinary collaboration is going well when everyone is able to safely, thoughtfully stir the pot.

In Defense of Pot-Stirring

“To stir the pot is to be the arbiter of chaos.” - what I used to think.

In reading a couple hundred papers over the past four months — on interdisciplinarity, group decision making, and responsible AI research and practice — I’ve learned that the entire trajectory of a conversation can change because (a) one person becomes aware internally of a potential knowledge gap no one else noticed (b) and that person is willing and able to surface said gap externally in a way that others can respond to & build off of.

I call these moments of “rupture”.

Moments of Rupture

Rupture is a concept I learned from Alex Gillespie, my professor/advisor/mentor in grad school. A moment of rupture is when one person becomes aware of a knowledge gap no one else seems to have noticed and decides to bring it to others’ attention. These moments are small but crucial in order for people with differing perspectives, or with access to different types of knowledge, or who are articulate in different languages, figuratively and/or literally, to work together. It is only once the rupture is surfaced, that repair (explained a bit below, but is a topic for another post) is possible.

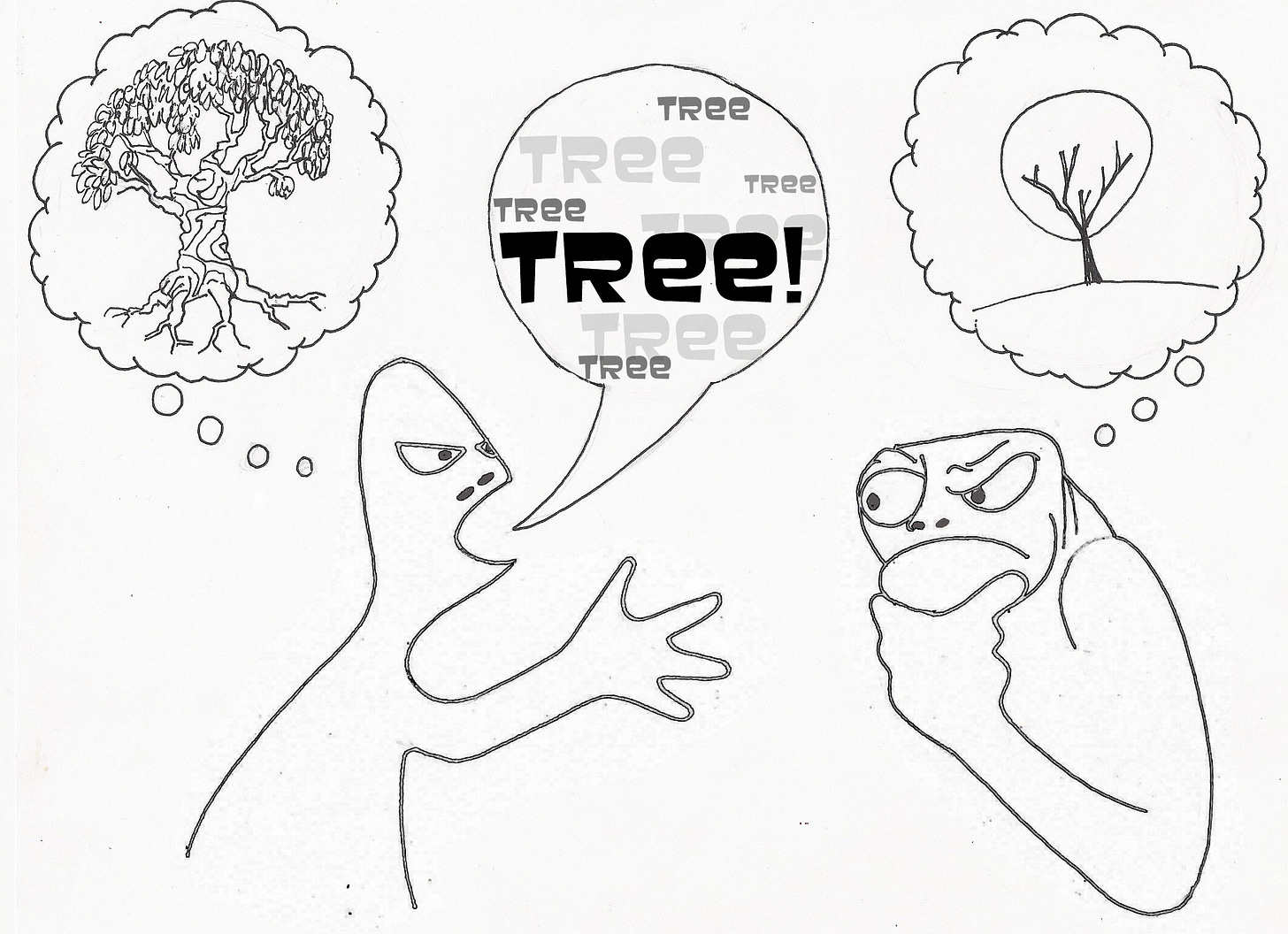

Without rupture there can be false harmony (people think they’re aligned but are not) or false discord (people are aligned but think they aren’t). False harmony and false discord are undetectable. Which makes them dangerous for the collective. This is ironic because rupture, for the individual, often feels dangerous, unsafe, and uncomfortable.

There’s no published academic literature that focus on conversational rupture explicitly, but I can share an excerpt from this paper he coauthored with Flora Cornish*. So here are some examples of experiments from Alex and Flora’s paper in Social and Cultural Psychology that artificially create divergences in perspective, requiring people to communicate their differences in perspective:

Experimental situations are created in which there is a joint task with distinct social positions thus creating two different perspectives.

For example, each participant is given unfamiliar tangrams and, without seeing each other’s, one participant must communicate to the other their sequence of shapes (Clark & Wilkes-Gibbs, 1986).

Or each participant is given a map, and a Director must verbally guide the Follower through the map (Blakar, 1973).

Or, one participant is given a picture and they must verbally communicate that picture to the second participant who then has to draw the picture (Collins & Marková, 1999).

In each of these experimental scenarios, the researchers create a divergence of perspective, and then observe how the participants repair it and create mutual understanding. These experiments have revealed the intensely collaborative nature of communication.

Even when participants start out with massive divergences of perspective they work collaboratively to build a shared nomenclature and set of implicit assumptions which enable them to jointly navigate a task.

(Gillespie & Cornish, 2010: Intersubjectivity: Toward a dialogical analysis)

Designing for Rupture

I’m thinking a lot these days about what it means to create learning and work environments that support exploration and uncertainty. How do you make a space rupture-prone? How do you make it easy for people to “build a shared nomenclature and set of implicit assumptions” so that they can get through a difficult challenge together? It’s not enough for your teammate to message you “let me know if you need anything <33” on Slack. Or for a manager to say “I’m open to criticism; don’t be shy. Help me help you.” Or for a professor to say “There are no stupid questions! Come to office hours!”.

If an organization is serious about exploration and nursing uncertainty, that organizational structure must ensure that pot stirrers feel safe stirring the pot. If someone speaks up about a potential gap in knowledge or challenges a collective belief, but the organization’s infrastructure punishes them implicitly or explicitly, intentionally or unintentionally… a dangerous territory has been designed.

Whether a person’s fears are real (i.e. a healthy person in a toxic team environment) or imagined (i.e. a paranoid person in a healthy team environment)… the onus lies on the institutional design.**

When your team is full of people who can stir the pot, ask the stupid question, or stumble through a thought process out loud, it not only creates room for others to facilitate the conversation, but it normalizes rupture: the most important thing that can happen in an interdisciplinary, collaborative conversation.

Okay bye! - Kayla

*Dr. Cornish is another incredible professor at LSE who taught me qualitative methods in 2020 and also happens to be Alex’s partner. I only found out about ~3 months into working with each of them independently that they were coauthors of my very favorite paper. I shared this with my academic mentor (hi Cathy 😉) a week later who told me that they’re married. Isn’t that wild and beautiful and just… ugh 🥹.

**there’s a-whole-nother conversation to be had about who has input/agency to (re)design an institution (and then a-whoooole-nother conversation about which of those people can/should/must be responsible… that is in my philosopher friends’ territory 🙂↕️)

Frontal lobe just got a little bit more solid with this read. Thank you for sharing your thoughts!🫶🏾