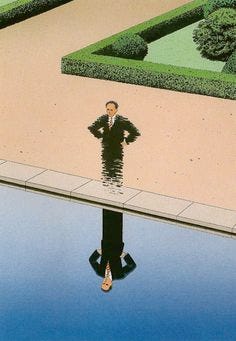

A mind studying The Mind™

on the existentially frustrating experience of being a social scientist in my 20s

In July, I officially entered my late twenties (!). Over the past couple of years, it’s been wonderful to experience the shift from trying to “discover my values” to, instead, making active decisions about the principles I want and/or need to live by.

This is not always a fun process. Multiple times a day, I catch myself doing things that don’t reflect my principles (for example: saying I like something when I don’t, saying I don’t like something when I actually do, offering advice to someone who didn’t ask for it, taking too long to reply to a text message, etc.). Moreover, I’ve increasingly found myself in situations where my values conflict, forcing me to prioritize what matters most in each context.

Ironically, while navigating this mental metacognitive obstacle course each day, I’m pursuing a PhD focused on understanding how people think and act.

Yes, I only arrived 27 years ago, and yet I’ve taken on the challenge of trying to unravel the complexities of human behavior that have puzzled us for millennia: why we do what we do, why we don’t do what we want to do, why we end up doing what we don’t want to do, and why we desire anything in the first place, etc., etc.

I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do. And if I do what I do not want to do, I agree that the law is good. As it is, it is no longer I myself who do it, but it is sin living in me. For I know that good itself does not dwell in me, that is, in my sinful nature. For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing. Now if I do what I do not want to do, it is no longer I who do it, but it is sin living in me that does it. - Apostle Paul, 57 AD

As I enter my second year of grad school, the irony has become more difficult to ignore: I am studying how people make decisions when my own principles sometimes feel like a moving target. But maybe that’s the point—the process of understanding others is deeply intertwined with understanding ourselves. Perhaps, it’s through this constant balancing act between self-discovery and self-determination that I learn “who I am” is something I actively choose to shape every day.

Being human while studying humans is inherently messy. We even use a term for this in my discipline: “reflexivity”. Reflexivity is about being conscious of how our own perspectives, experiences, and biases shape the research questions we ask, the data we collect, and the conclusions we draw. It’s a way of recognizing that our humanity is an unavoidable part of the equation.

Beyond mentions of reflexivity in the “Limitations” sections of our research publications, however, I’ve rarely discussed with my colleagues this potential relationship between (mis)understanding ourselves and (mis)understanding others. After all, who has time for an existential crisis during a lab meeting?

Instead, I’ve found some valuable insights on this topic through LinkedIn—one of the rare spaces online where researcher-practitioners and practitioner-researchers engage in meaningful dialogue. ;) To close this post, I want to share a LinkedIn post by Laurence Barrett that has been pinned to my desk for about a year. I’ve included a photo of the original at the very end and have taken the liberty of semi-paraphrasing it (sorry, Mr. Barrett!) to highlight the parts that have resonated with me the most:

The instrument through which we understand mind, is mind.

Our research studies fall somewhere along a spectrum:

At the conscious extreme we may believe that we are rational gods, knowing all there is to know. Here the boundaries of our present knowledge are the boundaries of all knowledge. We believe we can know the whole world through our ‘evidence’ and we believe that this world is unchanging. This place is science as religion and we defend it (somewhat paradoxically) with a great deal of emotion.

At the unconscious extreme, we believe that we are spiritual gods, feeling all there is to feel. Here the boundaries of our personal experiences are the boundaries of all experiences. We believe we can know the whole world through our experiences and our deeply felt superstitions. This place is religion as science and we defend it with a great deal of emotion.

In between is the uncomfortable reality of ‘not-knowing’. Here we have to accept that we cannot know all there is to know, and we cannot feel all there is to feel. This is an often humbling experience. It is a reminder that we are not alone and we are not really that clever. We are instead just beings investigating the parts of ourselves we’ve managed to understand (or those some of us think we have managed to understand - like love, grief, or what it takes to become a morning person).

The more desperately we cling to these parts and these explanations, the more we reveal ourselves, and the more we reveal the fear that the experience of ‘not knowing’ provokes in us.

To work with mind, we must be able to contain this fear, working with dynamic and lightly held hypotheses derived from an often chaotic combination of evidence and experience. We must draw from the broadest range of inspiration possible.

To contain our fear of the unknown, we must acknowledge our subjectivity. We must accept that the instrument through which we understand mind, is our own mind and we must become the first object for our study. We must observe ourselves in our work.

Okay bye!

- Kayla

Hey, I stumbled across your work and this is so beautiful, it was an nice touch to see a piece of scripture drawn from directly from the Bible written by Apostle Paul to the church in Rome( Romans 7:14-20).

Apostle Paul had this inclination in exploring the mind and how we have a limitation on understanding our mind as described by your work labelled by this continuum, the rational”, the “spiritual” and the “no clue/idk” region.

The deal with trying to understanding the mind is that we are beings trying to live out and understand this complex nature of our mind as described in your work, through the experiences we go through daily, so using our mind as an instrument to understand “the mind” is definitely something challenging.

Maybe the knowledge of a higher power,a divinity, can counteract this pitfall.

Thankfully, we had the opportunity to have a divinity walk amongst humanity and as described in all of ancient texts, his name is Jesus. Have a look, He might enable you to understand this existential crisis you might have regarding your work, potential renew your mind too in the same process ( Romans 12:2) ;)

Fantastic as always. "The process of understanding others is deeply intertwined with understanding ourselves." Much better explanation of reflexivity than any academic writing. I also struggle with this, but i don't have anything smart to add. Thanks for writing :)