06: power orientations (Estonia trip! and why knowing my relationship with power makes me a better colleague)

I was in Estonia this week; I had an epiphany about social science researchers' orientations to power

In this post, I share a bit about my trip to Estonia last week for a summer doctoral course on Participatory Design. The first half is a (non-)explanation of why I went and some photos of my time there. In the second half, I introduce a term, “Power Orientation”, that I came up with in a moment of epiphany. It’s helped me filter feedback from my peers and made me much better at giving feedback to others. Enjoy and please share any thoughts you have.

Estonia?

Estonia is a country in central Europe that was a part of the Soviet Union until the 90’s. It has a population of 1 million people and hands-down the cutest airport I’ve ever seen. Each terminal at the Tallinn airport had its own theme and/or a corporate sponsor. Some wonderful human has posted an ASMR tour of the Tallinn airport on YouTube. Enjoy.

Why was Kayla in Estonia?

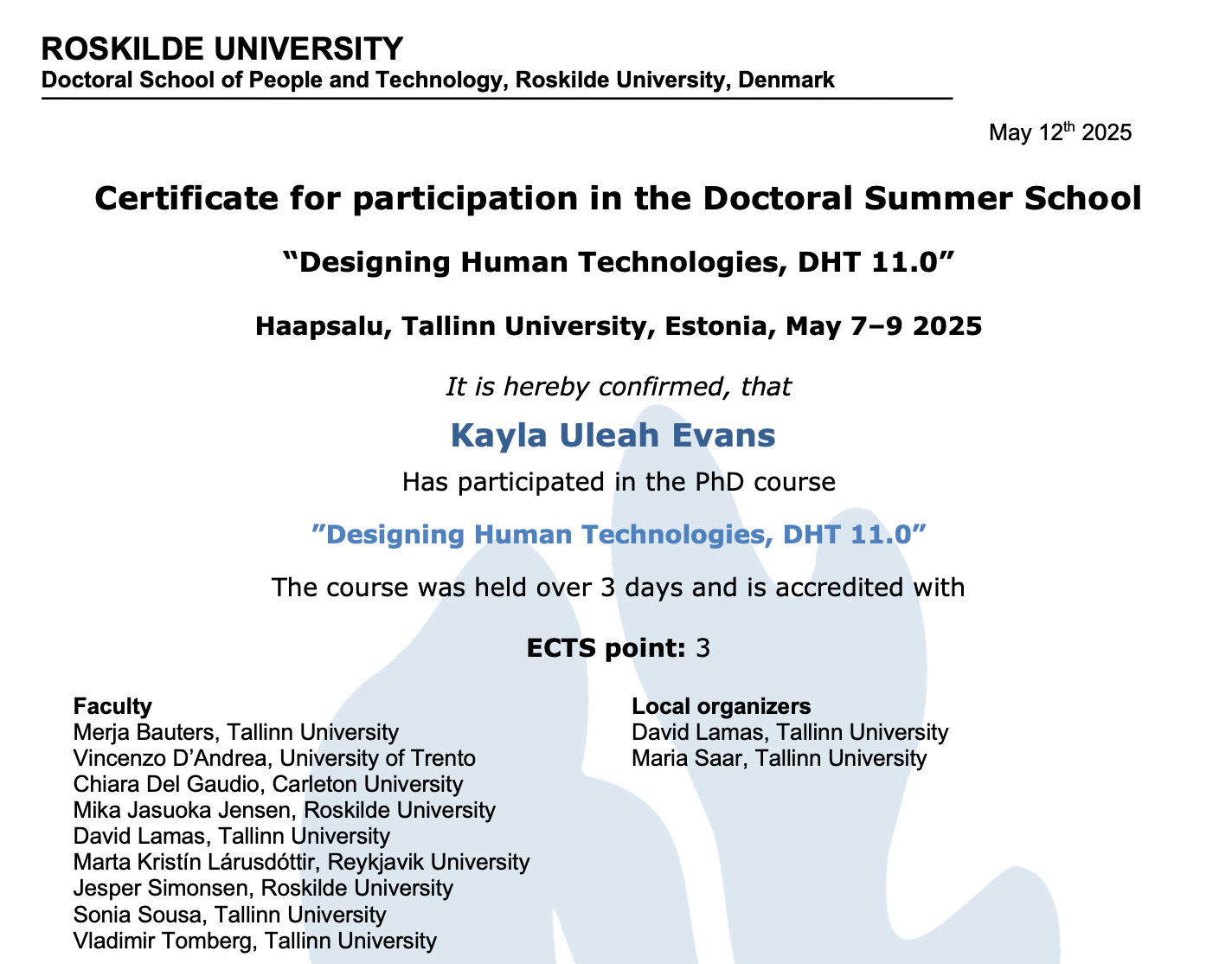

I went to Tallinn for a doctoral course called “Designing Human Technologies”. There, I presented and got feedback on my research on interdisciplinary expert collaboration. If you’re interested in my position paper, I’ve linked it here. I’m quite proud of it.

an aside: Going to Estonia for 3 days might seem random to you. That’s because it is. I learned upon arrival that I’m the only person who flew in from outside of central Europe. I was asked at least a couple times-a-day, “Oh… why did you fly all the way here? Are you just here for this?”. Every time, I’d respond “hmm…yeah. those are great questions.” and we’d laugh. one new estonian friend said, “well, I guess now it’s your job to figure out why you’re here”.

What’s makes it even funnier is my half-hearted effort to get there… Upon receiving the email of my acceptance a few weeks ago, I’d forgotten I’d applied, didn’t recognize the email, and then reported it to Georgia Tech as spam. It was only when the program director emailed saying my invitation had been revoked that I remembered what it was.

I kindly asked if I was still allowed to attend. They responded immediately saying that a spot had opened and I had 24 hours to take it. At hour 72-ish, I finally saw that email (it was my qualifying exam week & my email was the last thing on my mind). Feeling frustrated with myself (but also relieved that I wouldn’t have to book a last minute trip to Estonia), I apologized to the organizer for fumbling the bag twice. I said I’d look forward to next year. And then days later…

My God is a God of third chances! Apparently, it was meant for me to take a round trip flight to Estonia for a 3 day doctoral course. So I went! Really grateful to my advisor for funding my travel & accommodation.

Estonia was beautiful.

It’s this really lovely mix of providential and hip. Here’s a gallery of photos I snapped while I spent my first day exploring Old Tallinn.

While shopping at markets & dilly-dallying around the city, was reminded of just how much I love art. This is the first time in a couple of years that I’ve traveled completely alone outside of the US. I let myself follow nothing other than my curiosity. It tended to lead me to things I loved as a child - arts and crafts, historic buildings with intricate designs, the notepad sections of book stores, and slow-dripping a historical fiction book.

I enjoy finding local bits and bobs for my loved ones just as much as I love exploring cities themselves. Here’s one thing I brought home for myself, by a local artist:

and how was the course?

The course was excellent! I learned loads about Participatory Design and met some really brilliant colleagues.

Who was there?

There were about 30 PhD students total.

How did we prepare?

Before the course, we sent a “position paper” detailing our research and what we wanted feedback on

So it’s a conference?

Not quite. Much smaller-scale.

We were split into groups of five, and had the guidance of 1-2 senior experts in Participatory Design

Each participant presented the work of another person in their group. This gave us the chance to get to know a colleague’s work, and to experience seeing another person present our work before knowing anything else about us or our research.

In these conversations, we gave our feedback and advice on how that person could use Participatory Design methods. This is where the conversations got incredibly interesting — not just in their content, but in how the sessions went.

How did they go?

The presentation/feedback sessions were extremely helpful! But not in the way I expected. In the end, I think I learned more about being a good colleague than I learned about being a good researcher.

I’ll share an anecdote that led to an epiphany:

At one point on the final day of the course, my group-mate Leo was getting pressed for not involving users more directly in his educational video game research project. I understood the critique, but it felt like the wrong question.

In a moment of mid-conversation frustration over the misalignment between Leo’s goals and our feedback for him, I opened ChatGPT. I struggled to turn my feelings into a question, so I just told it “i think there are different types of researchers/goals… some of us want to learn, some of us want to build, some of us enjoy collecting data… and this seems to impact how we choose to phd”:

After hyping me up for my “powerful insight”, Chat echoed my observation in clearer language and suggested “archetypes” to help me make more sense of what I was noticing.

For Leo, the point of his research was different than the point of mine, and even more different than the points of the other students’ in the room. Leo’s work wasn’t meant to uplift a community or shift a system. He was building a technical intervention that had secondary impact on students’ ability to learn computer science. Yes - his work has downstream influences on the accessibility of higher education, and equity of computer science courses that tend to disproportionately push girls out of CS. And yes, these are motivators for his doing this work. But he was doing a PhD (rather than being a CS teacher), because he’s primarily motivated by the mode through which he can do this work. So, yes, while his work under-supported group (CS ed students in higher education who leave CS out of frustration), it didn’t mean that his primary goal was to uplift that group or disrupt CS education as a whole.

As the conversation continued, it became clear to me that Leo probably shouldn’t shoehorn Participatory Design into his project just because he’d flown to Estonia to talk about it. I riffed a bit more with Chat and other colleagues about the paradox of being researchers who care about our participants, but take completely different approaches to participatory design methods.

Here are some in-progress reflections from those conversations:

Understanding your own research motivations is crucial if you want to know whose advice or resources to accept, and which to politely decline. And yet, in the decade since I entered academic research, I’ve almost never been asked why I’m doing the research I’m doing. Knowing this matters. It shapes who you collaborate with. What kinds of funding you pursue… how you spend your summers… or whether you apply to academic jobs at all.

I started thinking about what each of us was using our PhD to do, and the mode through which we were engaging with power. These thoughts evolved and became the basis for something I’m calling our Power Orientations, or the way we orient ourselves toward power in our research. It’s very useful for us to have answers to the following questions:

Who are you trying to empower?

What kind of power do you think they should have?

Are you diagnosing an imbalance or actively intervening?

Are you observing, or are you designing?

And if you’re designing, is your goal to prompt reflection, enable resistance, or eliminate the issue altogether?

I don’t think we’re avoiding these questions on purpose. But I do think our systems don’t make space for them. Without space to ask why we’re doing this in the first place, we don’t have the tools to decide whether we should be doing it at all or whether there’s another kind of work that would let us engage power much more honestly and effectively.

For myself, I’ve had to learn and re-learn my approach to addressing systems of power. I’m not necessarily interested in improving the circumstances of a certain user group if I think we’re conceptualizing their problem in the wrong way. But when a peer asks for feedback on their project that is working to improve the circumstances of a user group, it’s not helpful for me to advise them on revisiting their problem statement.

Knowing my own power orientation helps me be a better colleague. Instead of defaulting to my own starting point, I can ask: What are they trying to do here? What kind of power are they working with or working against? Once I understand that, I can give feedback that’s actually useful to them; I’m more likely to give guidance that moves their project forward, not my own.

Sometimes that means holding my tongue (so, so hard). Sometimes it means still doing what comes naturally to me: offering a framing they haven’t considered. But either way, it means I’m responding to their orientation, not projecting mine onto their work.

I hope this framing continues to make me a better collaborator, and also helps me recognize when someone’s feedback, even if well-intentioned, just isn’t for me.

P.S. You may have noticed the name of my substack has changed! It’s now called “Terms & Conditions”. I started writing here in 2022. At the time, I needed this space to be a living lab notebook for my observations on human social behavior. It’s since evolved into a collection of writings about those observations about the human condition and a growing lexicon of terms (e.g. container theory, internal ruptures, and — now — power orientations) I’ve created to help me talk to others about these hidden, non-intuitive patterns more easily. Welcome (back) to T&Cs. :)